With just seven weeks to go until Parliament is dissolved (at the end of March) for the general election campaign proper, and the Ministry of Injustice fully occupied trying to work out the correct burden of proof in criminal trials, it is now safe to assume that the Ministry’s long-promised review of ET fees is not going to happen this side of 7 May.

Having been busy “finalising” the scope and timing of the review as long ago as June 2014, by last month the Ministry was only “considering” these tricky concepts. And, while seemingly powerless Liberal Democrat ministers have since early 2014 used the review as a shield to cower behind whenever the issue of fees has been raised with them in parliament or in public, at a recent Working Families policy conference BIS minister Jo Swinson didn’t even try to do so when the impact of fees on parents’ ability to assert their flexible working rights was raised from the floor by Bronwyn McKenna of UNISON.

However, timing aside, finalising the scope of the review is not something that should have detained even the lowliest Ministry official for very long, as the job was done even before the fees regime came into force in July 2013. As previously noted elsewhere on this blog, a plan for the review was set out in an annex to the Ministry’s final regulatory impact assessment of the fees regime, issued in May 2012:

HMCTS will review ET and EAT fee rates to evaluate the impact of the introduction of a fee in this jurisdiction, and to compare against the behaviour predicted by our economic model. We will seek, wherever practicable, to align any proposals for improvements to the system with future reviews of fee levels. Any changes to fee levels will be made through legislation.

The review will seek to:

- Ensure that those who use the ET system, and can afford to pay, do pay a fee as a contribution to the cost of administering their claim/appeal;

- Ensure that the remissions system ensures that only those who can afford to pay a fee do so;

- Ensure that the fee charging process is simple to understand and to administer;

- Examine impacts on equality groups; and

- Verify the amount of fee income raised against the models presented in the Impact Assessment and quantify any operational savings.

The first thing to say here is that “economic model” was a somewhat inflated way to describe the wild guesswork that made up most of the Ministry’s impact assessment. Whatever, since there is no evidence of workers using the ET system without paying a fee (or obtaining full remission), we can tick off the first bullet point. There is some evidence (and the Ministry appears to be sitting on further evidence) that the remissions system is doing very little indeed to protect access to justice, not least because the criteria and process for obtaining fee remission are anything but simple – the application form and guidance notes run to 30 A4 pages. And the Ministry has recently published figures on both fee income (less than predicted) and the associated operational savings (greater than predicted).

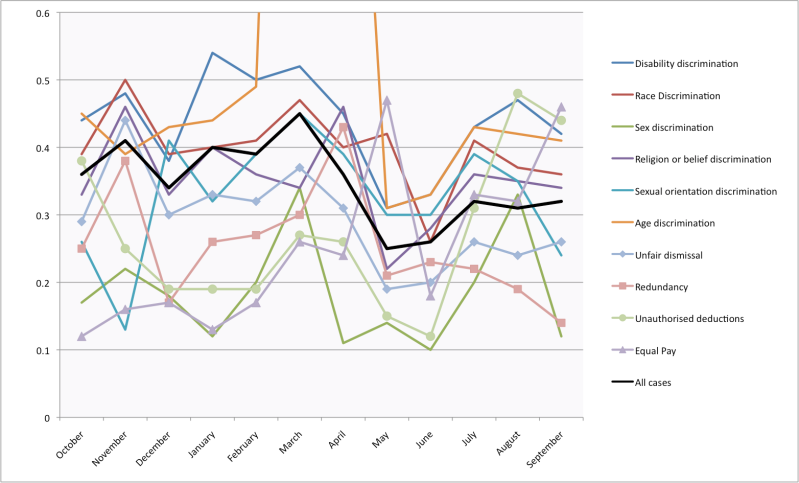

As for the “impacts on equality groups”, the substantial fall in the number of discrimination claims since July 2013 is well documented, with the figure for sex discrimination claims most commonly cited by MPs and others. But I thought it might be illuminative to apply the exercise I undertook in my last post – plotting claim numbers in the 12 months up to September 2014 as a percentage of the average over the 12-month period July 2013 to June 2013 – for the main jurisdictions. And this chart is the result.

Note that, apart from the black line, which is all cases (i.e. singles + multiple claimant cases), the figures used here are for jurisdictional claims, with an average of about 2.1 jurisdictional claims per case. And yes, age discrimination claims really did shoot off the scale in March and April 2014, presumably due to one or more large multiple claimant cases (or data entry errors by HMCTS).

So, apart from “urgh what a horrible mess”, what can we say about this chart? I hesitate to say too much, and would be very interested to hear the views of others (post a comment!), but I think it confirms what we already knew: that women have been big losers under the fees regime, with both sex discrimination and equal pay claims depressed markedly more than those in other jurisdictions.

That said, there has been something of a recovery in equal pay claims, and in claims for unauthorised deductions, since the introduction of Acas early conciliation in April 2014. I leave it to my clever long-lost twin, Michael Reed of FRU, to explain what that’s all about.

Is there any comfort to be drawn from this chart by, say, a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Justice? I guess such a person might note that the number of claims in most discrimination jurisdictions other than sex discrimination has been depressed a little less than in some of the other main jurisdictions, such as unfair dismissal and unauthorised deductions. But I really don’t think that’s anything to crow about. The number of claims in those jurisdictions has always been relatively small (and is now very small indeed), and at such a low level of claims we might expect a slightly lower price elasticity of demand in those jurisdictions. We can think of this as the ‘How low can you go’ theorem.

And of course, as shown by this excellent new report from Citizens Advice Scotland, every time a valid claim is not brought due to the cost of fees, an employer gets away with unlawful discrimination. What the chart really confirms is the shallowness of the Coalition government’s stated commitment to tackling the discrimination that remains all too rife in UK workplaces. In a new Government Equalities Office guide to tackling sex discrimination in relation to pay, for example, equalities minister Nicky Morgan states: “I want women to feel able to hold employers to account if they feel they are not being paid the same as their male colleagues.” Yet, as the guide quietly acknowledges, “if your employer still refuses to pay you equally,” then the only way to ‘hold your employer to account’ is to issue and purse an ET claim.

Limit access to that means of holding employers to account with ET fees, and the unequal pay that feeds the gender pay gap will take even longer to eliminate, to the detriment of all.