In February, when rejecting UNISON’s judicial review of the employment tribunal fees regime introduced last July – on the grounds that it was simply too early to reach a firm conclusion on the impact of the fees, the only available statistics being provisional figures for the month of September – the High Court noted that “if [these provisional figures] are anything like accurate, then the impact of the fees has been dramatic”. And the judges suggested that, should the Lord Chancellor’s optimism that the number of ET claims would soon bounce back to more ‘normal’ levels prove unfounded, then they would “expect the Lord Chancellor to change the [fees regime] without any need for further litigation”.

Within weeks, the accuracy of those provisional figures was confirmed, with tribunal statistics for the three-month period October to December (Quarter 3 of 2013/14) showing a dramatic fall in the number of ET claims by individual claimants, from an average of 4,460 per month in the nine months before the introduction of fees in July 2013, to just 1,000 in September, 1,620 in October, 1,840 in November, and 1,500 in December.

UNISON has since been granted permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal, but as of today the ball is back in the Lord Chancellor’s court, with the latest set of quarterly tribunal statistics – for the period January to March 2014 (Quarter 4 of 2013/14) – showing no significant rebound in the level of ET claims since December.

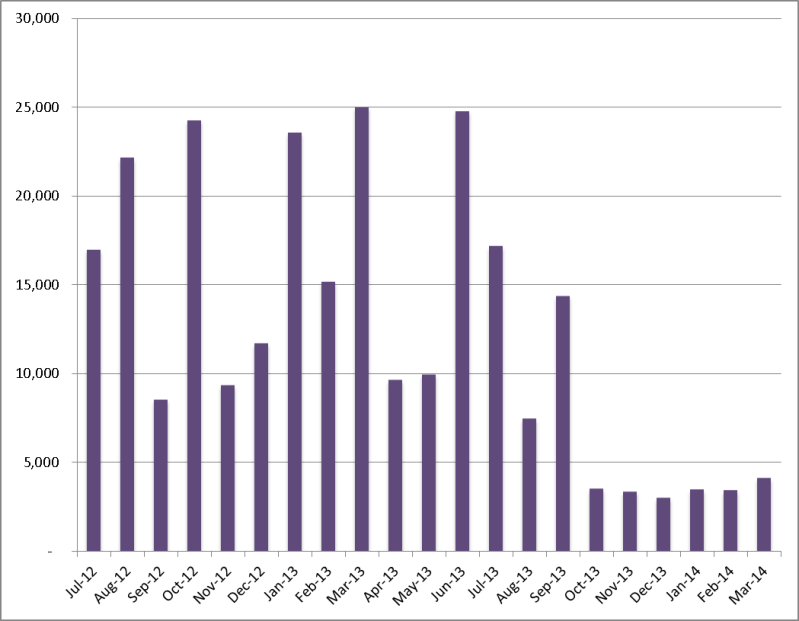

The headline number of ET claims, which includes both single and multiple claims and which was down 78 per cent in Quarter 3, was down again in Quarter 4, by 83 per cent compared to the same quarter a year ago. Based on past experience, this is the figure that will dominate reporting of the new set of statistics. However, as is clear from the following chart, this figure is arguably not the most reliable indicator of the impact of fees, given its evident volatility over time due to large variations in the monthly number of multiple claims (that is, the total number of claimants in multiple claimant cases). That said, the impact of fees seems reasonably clear.

Chart 1: ET claims (singles & multiples), July 2012 to March 2014.

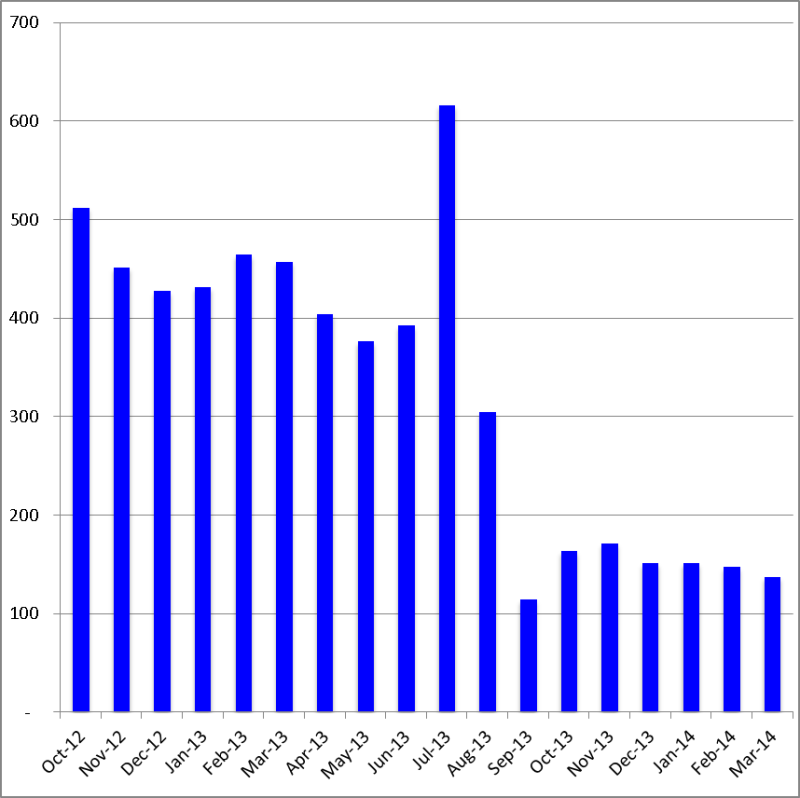

The impact of fees since July 2013 is much clearer when we look at the number of single claims by individual workers, which was down 64 per cent in Quarter 3, and was down again in Quarter 4, by 58 per cent compared to the same quarter a year ago. While the Ministry of Justice will no doubt be highlighting the 13 per cent increase from Quarter 3 to Quarter 4, at 1,763 the average monthly number of claims in Quarter 4 is still just 39 per cent of the average over the nine months prior to July 2013 (4,460).

Chart 2: ET claims (singles), October 2012 to March 2014

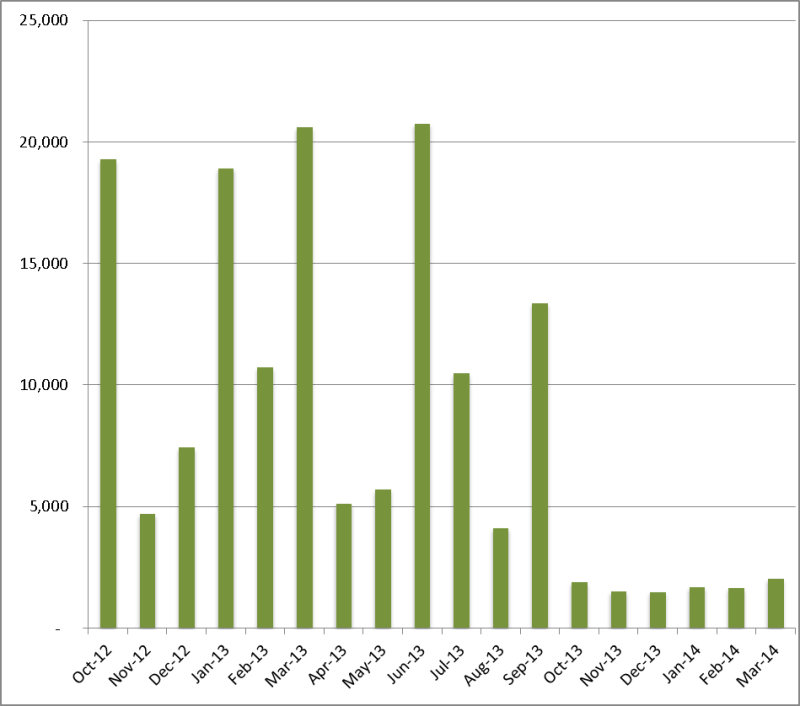

Somewhat surprisingly – to me at least – the number of multiple claimant cases, which in theory should be less affected by fees, has also fallen dramatically since July 2013. Down by 65 per cent in Quarter 3, from 1,390 to 485, the number of such cases was down again in Quarter 4, by 68 per cent compared to the same quarter a year ago.

Chart 3: ET multiple claimant cases, October 2012 to March 2014

Given that claimants in the very largest multiple claim cases each pay only a tiny fraction of the fees, the most obvious explanation for this fall in the number of multiple claimant cases would be that fees have cut out those cases with relatively small numbers of multiple claimants. However, this would imply a significant increase in the average number of claimants in multiple claimant cases. And, as the following chart shows, with the exception of September (when, presumably, there were one or two very large cases), the average number of claimants in multiple claim cases has not only not risen, but has actually fallen since July 2013.

Chart 4: Average number of claimants in multiple claimant cases, July 2012 to March 2014

So, something else would appear to be going on here. Have the unions run out of equal pay cases?

Indeed, for me the main story from this latest set of statistics is that fees have had a dramatic impact not just on the number of single claims by individual workers, but also on the number of multiple claims and multiple claimant cases – which, in theory, should have been much less affected by fees.

Chart 5: ET claims (multiples), October 2012 to March 2014

All in all, it’s hard to see how the Lord Chancellor can credibly deny that the introduction of hefty, upfront fees in July 2013 has had a dramatic impact on the number of claims – both singles and multiples. Which means, if he does not now reform the fees regime (and substantially reduce the level of fees), he is likely to have to do so following an embarrassing defeat in the Court of Appeal at the hands of UNISON later this year (the appeal is currently scheduled for hearing sometime between 10 September and 10 December 2014).

The incredible shrinking fee remission fig leaf

In response to extensive criticism of the fees regime since July 2013, ministers have argued that access to justice is protected for low-income claimants by the associated fee remission scheme. However, the only figures on fee remission applications that the Ministry of Justice has been willing to release to date – covering the period up to 31 December – suggest that only about six per cent of all ET claimants obtain any fee remission.

According to these figures, provided by the Ministry in response to a series of parliamentary questions by shadow justice minister Andy Slaughter MP, just 600 “individuals or groups of individuals” were granted fee remission between 29 July and 31 December, while 1,800 fee remission applications were rejected. And in that period there was a total of 10,208 single claims (9,305) and multiple claim cases (903). So remission was applied for in just 23 per cent of all cases, and three out of four of those applications were rejected.

Yet as recently as September 2013, in its final Impact Assessment on the revised fee remission scheme, the Ministry of Justice suggested that 31 per cent of all ET claimants would be eligible for full (25 per cent) or partial (six per cent) fee remission.

In short, the fee remission scheme has so far proven to be a very small fig leaf indeed, and seems unlikely to provide the Lord Chancellor with much cover in the Court of Appeal.