Over the past couple of months, more than one legal commentator has painted the new(ish) secretary of state for justice, Michael Gove, as a bit of a good thing. Admittedly, Attila the Hun would have seemed a breath of fresh air after the not exactly cerebral Chris Grayling. But, since his appointment in May, Gove has won plaudits for swiftly reversing the ludicrous prison book ‘ban’, for highlighting the need to modernise our ridiculously antiquated court procedures, and for hinting he may be something of a penal reformer. Even I have found myself in solidarity with him on decriminalisation of TV licence fee evasion.

So far, however, I have not been tempted to join the emergent Michael Gove Fan Club. Because Gove’s few comments to date on employment tribunal fees, and their devastating impact on workers’ access to justice, suggest his approach to the issue is no more intelligent than that of his predecessor.

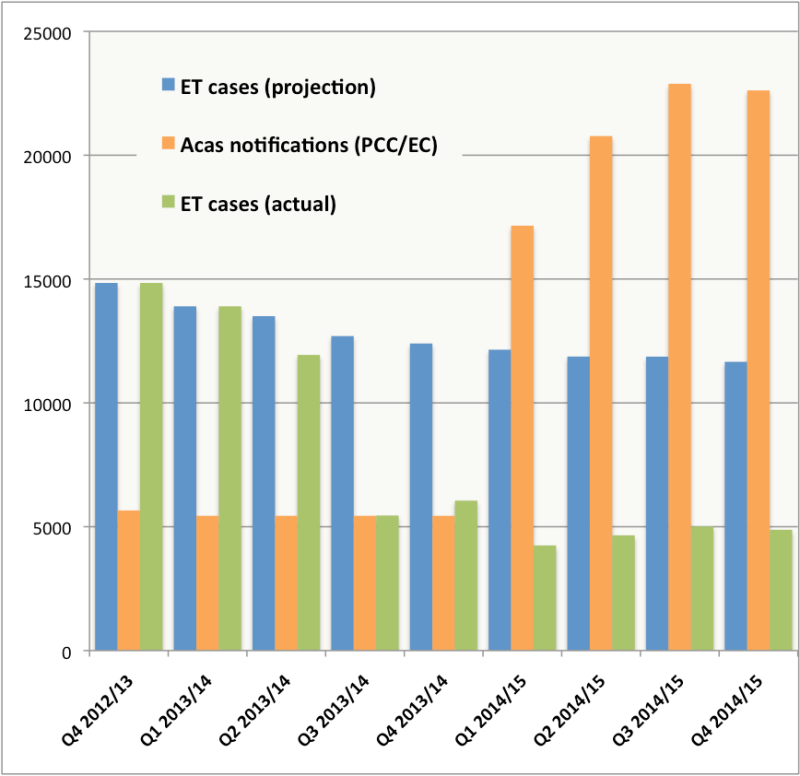

In July, when giving oral evidence on the work of his Ministry to the justice select committee of MPs, Gove chose not to deploy any of the Ministry’s lame excuses for the precipitous fall in ET case numbers that followed the introduction of upfront fees of up to £1,200 in July 2013 (“historic downward trend” in case numbers, improving economic conditions, and the introduction – nine months after fees – of ‘mandatory’ Acas early conciliation). However, the supposedly clever justice secretary indicated he will only “revisit” the decision to introduce such prohibitively high fees if “one can point to examples of rough justice – a simple reduction in the numbers of people going to employment tribunals is not in itself proof that there’s been any injustice visited on anyone.” Pressed on this point, Gove responded by saying:

I think that I’d have to see whether or not there was an example of people – or an individual – who’d been dismissed, who hadn’t had appropriate access to justice as a result, and that hard case – or those hard cases – would lead me to think again. But at the moment, what I think is likely to have been the case, is that the bar has been set at a high level, absolutely, but there is no evidence yet that the bar being set at a high level has meant that meritorious claims by people who feel [sic] they’ve been discriminated against aren’t being heard.

Tantalisingly, this suggests that Gove could be persuaded to think again by just one single example of ‘rough justice’, but we all know that’s not the case. The justice secretary would of course say ‘well, that’s only one example, I’m not changing the fees on the basis of just one case. I need to see more.’

But it’s the final part of Gove’s comment that gives away the real intellectual incoherence of his position. For there is in fact no shortage of evidence of people who feel that they’ve been discriminated against (or otherwise unlawfully treated) by an employer, but who say they have been deterred from seeking justice through the tribunal system by the fees. As long ago as July 2014, Citizens Advice published an analysis of 182 potential tribunal claims dealt with by its local offices (formerly known as Citizens Advice Bureaux), showing that 34 potential claimants assessed by their employment law advisers as having a better than even chance of success in the tribunal were put off from pursuing a claim by the fees.

In a recent blog for Working Families, I myself cited the example of ‘Martha’, from the casework of the Working Families legal helpline in (late) 2013. The helpline’s advisers considered ‘Martha’ to have very good grounds for a tribunal claim, but ‘Martha’ was adamant that paying fees of up to £1,200 was not a practicable option for her: “I simply don’t have that sort of money – I’ve just been on maternity leave!” And the report of the helpline’s casework in 2014 includes the following example of apparent ‘rough justice’:

‘Denise’, employed on a zero-hours contract, had had her regular working hours substantially cut since she had taken time off for a pregnancy-related illness. When she had challenged her employer, pointing out that several new staff had been taken on recently, she was told “we need people we can rely on”. The helpline team advised Denise that her treatment amounted to pregnancy discrimination, but Denise said there was no way she could afford to pay the fees of up to £1,200 to pursue a tribunal claim.

Maybe Gove himself has never seen such examples of apparent ‘rough justice’. But we know his Ministry officials and legal counsel have, and we know their response. The 34 Citizens Advice cases they dismissed out of hand, stating – in October 2014, in their detailed grounds of defence of UNISON’s application for judicial review in the High Court – that “the methodology of the study is such that one cannot be confident of its reliability”, and that “whilst the advisers doubtless make a conscientious assessment of the likely prospects of success for their clients, the fact is that, ultimately, the advisers’ assessment is not the most objective one as they have only heard their client’s viewpoint, without the input of the defending employer.” And no doubt they would say the same of the Working Families helpline advisers, and their clients ‘Martha’ and ‘Denise’.

And the fact is, the Ministry mandarins are right. Because, as noted just last month by no less an authority than the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills, “only an employment tribunal can determine whether unlawful discrimination or unfair dismissal has occurred”. And, by definition, the potential but ‘deterred by fees’ claims of ‘Martha’, ‘Denise’, the 34 Citizens Advice clients, and any number of others whose cases have been highlighted over the past two years will never go near an employment tribunal.

So, dozens, hundreds or even thousands of examples of apparent ‘rough justice’ could be put before the justice secretary, but he will always be able to say, in each and every case, ‘but we don’t know that the claim is meritorious, as we haven’t heard the employer’s side of the story’. So he will never have to accept that there has been even one case of genuine ‘rough justice’, and he will never be placed in a position where he has to “think again” about fees. In short, the evidential bar for the Ministry’s post-implementation review of the fees has been set impossibly high, and not even an Olympian case study-gathering effort by critics such as myself (and an awful lot of employment lawyers) would make any difference to the ideology-driven outcome.

And of course, unless Gove is a lot less cerebral than his reputation suggests, he must realise this himself. Which means his response to the justice select committee in July was not just intellectually incoherent. It was grubbily dishonest.